I hope you all are finishing the year strong in anticipation of that nice long winter break coming up in about a week! Take the time to rest up, see family and friends, and stop thinking about school for awhile. You've earned that! Once rejuvenated, however, you should take some time to reflect on what went well and what didn't go so well in the classroom. I have three things for y'all to keep in mind as you think about how to improve your classroom.

1. Do I have enough rigor in the classroom?

When designing assessments, unit plans, and everyday lesson plans are you providing your students enough challenge? Many times problems with classroom behavior stem from a lack of challenging, engaging, and standards-driven instructional activities. Keep in mind that you don't want to give your students a task that they can't possibly complete or one that they can complete without your guidance. Rather, you should plan lessons that work within your students' Zone of Proximal Development (tasks that students can do with teacher guidance). "Rigor" means something different for each teacher's classroom, so we will be offering guidance what rigor could look like in your classroom with next quarter's professional development courses including Understanding by Design.

2. Do my students have a voice in the classroom?

Are you allowing your students to present opinions and then justify them? Are you asking open-ended questions, questions with no definite answers, that allow your students to critically think? Asking students identification and application (Depth of Knowledge level 1 and 2) questions is important in order for them to understand your content. However, our students need to be asked their opinions on your subject matter so they can personally connect the content with their everyday lives. Their will be PDs next quarter addressing how you can give your students' a voice through their writing, discussion, and projects.

3. Am I implementing culturally-responsive teaching in the classroom?

Culturally-responsive teaching is the idea that we understand our student's culture, the highlights (strong sense of family, church community, etc.) and low lights (racism, de facto segregation, etc.) of their environment. Then, we incorporate that knowledge to make pertinent lesson plans that help our students celebrate their culture but also think critically about how the problems in their community. Next quarter, TFA Humanities is going to be offering PDs on how to use culturally-responsive teaching in the classroom, so keep a lookout for those offerings in January. Also, the PDs will address the question of why should I be teaching culturally-responsive teaching even if I do not consider myself part of my students' culture?

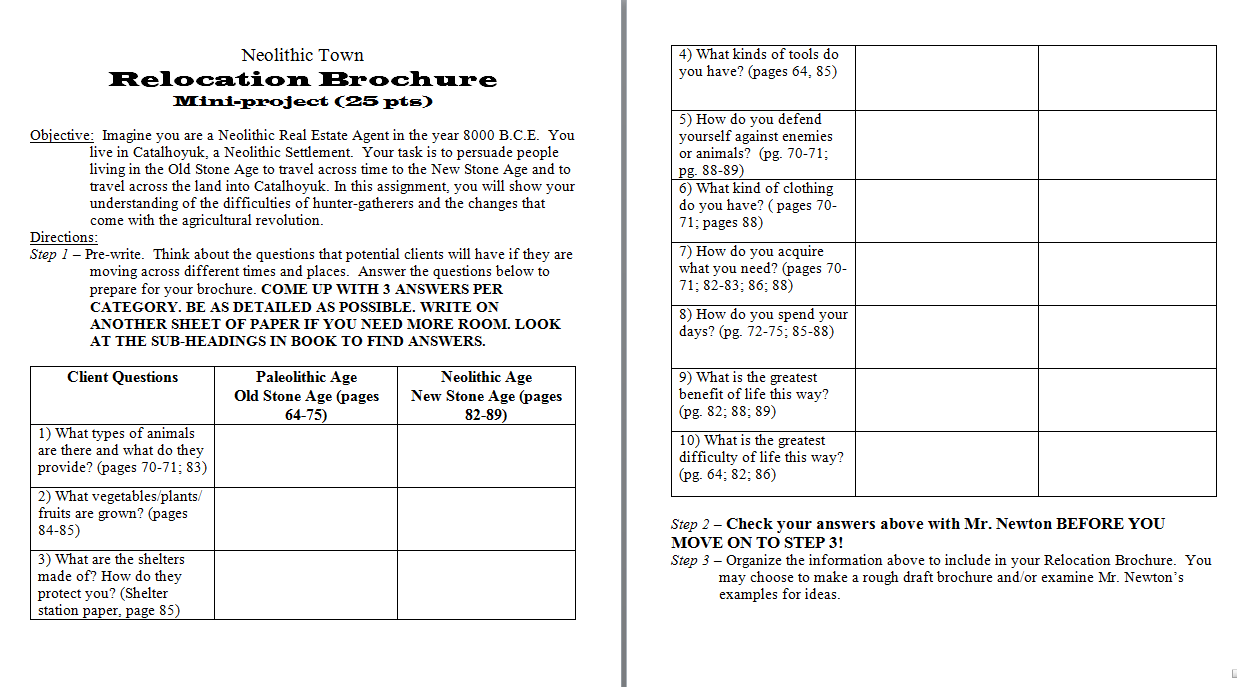

Charlie Harcourt, a seventh grade world history teacher at Solomon Middle School, has been doing some great things with project based learning in the classroom. Charlie's project ideas could be used to provide a rigorous, culturally-responsive instruction in your own classroom that allows your students to have a voice. Here's what Charlie has to say about project-based learning:

"I chose to write a post on project based

learning in Social Studies classrooms because of the long lasting effect that

it can have on the creative development of students. Project based methods can

present the same information to satisfy a content-based objective, but reach it in a

way that gives students a sense of independence, allows them to utilize

multiple senses and intelligences, and creates a more joyful learning

environment for everyone. I want to stress three key points to sell the use of

projects in Social Studies, and then address a few of the pushbacks and

cautions that could exist.

The first point is the ability for

content, presented or practiced in a project-based manner, to stay with students

longer. If I were to make a list of the lessons/activities that I remember from

school, all the way from Kindergarten to my last semester at Green Mountain

College, I would not be able to list any objectives, recite any vocabulary, or

summarize a lecture. I could easily describe the wigwam we built in Ms.

Conway’s class, the origami that we did in Ms. Craig’s, the play about Medieval

Life from Ms. Jentis, the live-action Odyssey game from Mr. Whitney, or the

presentations and mock-trails from Mr. Ashley.

Those are the lessons that stand a decade or more later; those are the

teachers that I remember; and those are the lessons and teachers that made me

excited to learn.

Now that I am in my 2nd

year of teaching 7th Grade Social Studies at Solomon Middle School

in Greenville, MS, I see my students from last year whenever I walk down the 8th

grade hall. The first thing they usually ask is “are those 7th

graders worse than us?” But the second question is often about one of the few

projects that I attempted to facilitate or assign last year. The students ask, “Did

y’all mummify those apples?” “You gonna do that water thing with the straws

again?” “They get to make the Social Studies boards?” This shows me what sticks

out in their minds and what they carry with them to the next grade and onward are

the projects we did together. This is part of what has motivated me to continue

and expand my use of various projects, experiments, presentations, and research

assignments in my class this year.

The second reason to try projects

in any classroom is the opportunity for students to experience a sense of creativity,

independence, and responsibility. I see so much of a student’s personality and

individuality come out in the projects that he or she completes, since a sheet of notes doesn’t tell me any more about a

student than the quality of his/her handwriting. When I read through the “Make

Your Own Civilization” project packets from

earlier this year, I felt like I was beginning to know my students through

their work. For example, I saw that one student named his Starkville, with a white

wolf on the flag, and he wrote “Winter’s Coming” in his made-up Stark language.

I was then able to confront him in class and say, “great job on the project,

stop watching “Game of Thrones”, you are way too young for that”. Bringing projects and hands-on activities to

the classroom also shows that you trust students enough to give them something that

is less structured than guided notes. It shows students that you respect them

enough to allow them to create something in your classroom. When we wrote

Cuneiform in salt-dough, I had nightmares of balls of dough and handfuls of

flour completely destroying my classroom. The maturity that hey displayed and

the joy they had in completing the assignment showed me that they deserved the

chance to be trusted and given responsibility to create something more

meaningful and more individual.

The third point is the idea that

projects bring rigor to a new height, whether judged by Bloom’s or any other

rubric. I admit that many of the projects that I have facilitated in my

classroom did not make a big jump in the rigor of my instruction. Playing with

clay, pouring water into a cup, taping up a salty apple, or drawing a picture

of a dream castle could honestly be done by some well-behaved preschoolers. The

opportunity for rigor really comes in the projects that allow students to

create something meaningful out of research that they have independently

completed. For instance, rather than teach the “fall of Rome” in a PowerPoint, lesson could be a student led investigation of a

great mystery, where students need to research and prove the true reason that

the greatest of all civilizations came to an end. They could debate it, present

it, write a defense for their findings, etc. This concept stretches a simple

objective into a process of investigating, applying, analyzing, and creating.

The criticisms that I wanted to

cover are time constraints, management, grading, and scaffolding.

Time Constraint: Welcome to the Humanities, you probably aren’t

state tested so congratulations, you have some freedom. It’s okay to take a few

days on a research project, stretch out an objective, make students write

opinion pieces, or get a little hands-on and messy in the classroom. Pick

something that you think is important and plan the time to stretch out an

objective into a project in your unit plan. It won’t be a waste of time if it

motivates and engages students.

Management: Behavior is probably the biggest reason why teachers

stay away from in-class projects or hands-on activities. If you structure it in

a way that allows the students to own the assignment, and still have very clear

expectations of each step and every rule, then it will work out. Make sure

groups are chosen by the teacher, problems are foreseen and planned for, and

directions are very clear. This should iron out most issues, but if some water or

clay ends up on the floor, it is sometimes just an unavoidable cost of doing

something hands-on and different in your classroom.

Grading: Use a rubric that emphasizes the key information or

expectations for the project, and use this to uniformly grade the assignments.

Create this when you create the project and then share it with your students as

part of the instructions. Students need to know how they are graded, and

teachers need to know how they are grading before collecting and/or completing

the assignment.

Scaffolding: Students need to have enough background content to

complete a project and make it meaningful. If they don’t understand the “why?”

behind the activity or project, then it is probably a waste of time. Projects can

be used to start a unit if they are set up like a research investigation, or

anticipatory activity. More likely this will be an alternative summative

assignment done at the end of a lesson that brings all of the essential skills

and content together in a creative manner. Make sure you pick out the key

prerequisite knowledge, expectations, and skills as you create the project

assignment and plan to teach these before you assign it.

Good luck to anyone trying projects in Humanities

classrooms!"